The United States has announced that it will deploy Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense system to the Republic of Korea. China has objected as it fears encirclement. The United States should continue to engage with China via official and other channels to mitigate concerns and avoid misperceptions.

On July 8, 2016, South Korea and the United States announced the decision to deploy Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense system to the Republic of Korea. The THAAD defense system will eventually be deployed and operated by U.S. Forces in Korea (USKF) “to protect alliance military forces … and not directed toward any third-party nations.” The purpose of the deployment was to establish a defense against the growing North Korean missile threat. China, however, has strongly objected. Chinese analysts argue that the THAAD radar will be able to surveil the entire Chinese mainland.

To reassure China that the range of the radar is limited, the United States had offered to provide a technical briefing to China on the system on the sidelines of the most recent Nuclear Security Summit. U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced: “We realize China may not believe us and also proposed to go through the technology and specifications with them … and prepared to explain what the technology does and what it doesn’t do and hopefully they will take us up on that proposal.” China declined the offer. Commenting on the issues, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman, Hong Lei, said that China does not view matter “as simply a technical one.”

Hong Lei is correct. The matter is not a technical one. China fears encirclement by the United States and its allies. It is not the THAAD radar that is impelling official Chinese objection. The radar would not be able to provide any new information beyond what the United States is already capable of obtaining. The U.S. early warning satellites can already track the heat signatures of missiles (including Chinese missiles) during their powered flight throughout the world. The THAAD radar would have to be able to observe “the decoy-deployment process of [Chinese] strategic missiles” after missile burnout to affect the Chinese deterrent in a meaningful fashion. It then has to continue to track and discriminate warheads and decoys. However, the operating parameters of the THAAD radar, proposed for possible deployment in South Korea, cannot permit it to track warhead and decoys launched along trajectories of Chinese Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) heading to the United States.

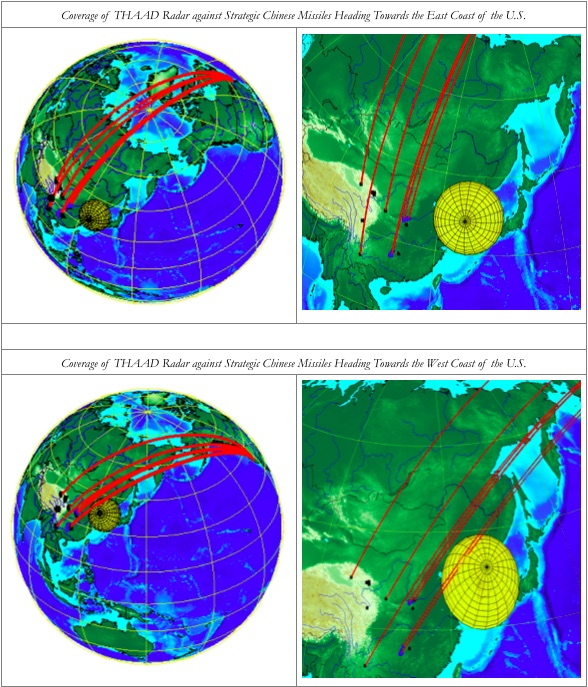

Presuming parameters within reasonable margins, a THAAD radar would have a maximum range of approximately 800 kilometers under even highly optimistic conditions. As shown in Figure 1 below, at a range of 800 kilometers, a THAAD radar deployed in South Korea would have essentially zero ability to track and discriminate Chinese missiles heading to the United States. Even one possible trajectory that might be momentarily observable could be lofted to avoid THAAD radar detection.

So, what is motivating Chinese opposition to the deployment of THAAD in South Korea? A prominent argument is that even mild U.S. missile defense postures in the region will over time accumulate increasing capabilities, and can, therefore, be quickly converted to a larger threatening posture. Some Chinese claim that the United States is beginning to form a balancing coalition with Japan and South Korea with the intent to encircle China with an interlinked missile defense system. Others argue that this possibility would fundamentally alter the strategic balance and stability between the U.S. and China and, in turn, could force China to increase its nuclear arsenal.

It is certainly in neither nation’s interest to foster such increases in nuclear weapons. Recognizing this, the U.S. has repeatedly pointed out that the regional missile defense systems do not and are not intended to alter the strategic stability. For example, the recent U.S. Ballistic Missile Defense Review stated: “Engaging China in discussions of U.S. missile defense plans is also an important part of our international efforts … maintaining strategic stability in the U.S.-China relationship is as important to the administration as maintaining strategic stability with other major powers.” The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review also made similar commitments.

The United States should continue to engage with the Chinese on both official and other channels to mitigate concerns and avoid misperceptions. Misinformation and misperception should not be fueling disagreements. However, such engagements also need to take into account Chinese offensive missile capabilities. Currently, ranges of Chinese missiles extend to U.S. bases as far away as Guam. China is also believed to have around 1,200 short-range missiles. China’s medium-range missile inventory may include as many as 400 CSS-6 missiles (with a range of 600 kilometers) and around 85 CSS-5 missiles (with a range of 1,750 kilometers). China also possesses a significant number of medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles.

Why does China need such a large arsenal of offensive missiles? One potential explanation is that these missiles could target U.S. forward-deployed forces, allied forces and bases in the region. Under such a scenario, missile defense in the Asia-Pacific region could offer limited defenses against Chinese short- and medium- range missiles, thereby strengthening regional deterrence and stability. If China, indeed, wants to limit U.S. missile defenses in the Asia-Pacific, it should cooperatively work to diminish the threats from all missile arsenals in Northeast Asia.

Jaganath Sankaran is a Research Scholar, Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland (CISSM), University of Maryland, College Park, USA. Bryan L. Fearey is Director, National Security Office, Los Alamos National Laboratories, Los Alamos, New Mexico, USA. They are the authors of “Missile defense and strategic stability: Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) in South Korea”, Contemporary Security Policy, 38, forthcoming. It is available here.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not represent those of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, the National Nuclear Security Administration, the Department of Energy or any other U.S. government agency.

Pakistan’s Nasr tactical nuclear missile platform is driving Indian debate on its current minimum deterrence doctrine. India’s minimum deterrence concept should indeed be reformulated for this new nuclear context. A new defense policy review should holistically integrate nuclear, conventional and subconventional approaches for reasons of effectiveness and continued public support.

Pakistan’s Nasr tactical nuclear missile platform is driving Indian debate on its current minimum deterrence doctrine. India’s minimum deterrence concept should indeed be reformulated for this new nuclear context. A new defense policy review should holistically integrate nuclear, conventional and subconventional approaches for reasons of effectiveness and continued public support.

In the 1999 limited war at Kargil, where a mix of Pakistani regular forces and jihadi proxies had captured parts of disputed Kashmir under Indian control, the U.S. directly threatened Pakistan with isolation unless it withdrew unilaterally. In the 10-month military standoff in 2001-02, and during the crisis that followed the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks, the U.S. forced Pakistan to acknowledge the flow of terrorists from its soil into India and to take action against some of these actors. It used Pakistani acquiesce, momentary as it was, to placate India. In 2001-02, it also reproved a recalcitrant India that refused to demobilize its forces by issuing travel advisories that advised U.S. citizens to avoid India, risking investor panic.

In the 1999 limited war at Kargil, where a mix of Pakistani regular forces and jihadi proxies had captured parts of disputed Kashmir under Indian control, the U.S. directly threatened Pakistan with isolation unless it withdrew unilaterally. In the 10-month military standoff in 2001-02, and during the crisis that followed the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks, the U.S. forced Pakistan to acknowledge the flow of terrorists from its soil into India and to take action against some of these actors. It used Pakistani acquiesce, momentary as it was, to placate India. In 2001-02, it also reproved a recalcitrant India that refused to demobilize its forces by issuing travel advisories that advised U.S. citizens to avoid India, risking investor panic.